The Long History of the Espresso Machine

In the 19th century, coffee was big business in Europe. As inventors sought to improve brews and reduce brewing time, the espresso was born

Each topic we tackle on Design Decoded is explored through a multi-part series of interlocking posts that will, we hope, offer a new lens for viewing the familiar. This is the second installment in a series about that centuries-old molten brew that can get you out of bed or fuel a revolution. Java, joe, café, drip, mud, idea juice, whatever you call it, coffee by any other name still tastes as bitter. Or does it? In our ongoing effort to unlock the ways design factors into the world around us, Design Decoded is looking into all things coffee. Read Part 1 on reinventing the coffee shop.

For many coffee drinkers, espresso is coffee. It is the purest distillation of the coffee bean, the literal essence of a bean. In another sense, it is also the first instant coffee. Before espresso, it could take up to five minutes –five minutes!– for a cup of coffee to brew. But what exactly is espresso and how did it come to dominate our morning routines? Although many people are familiar with espresso these days thanks to the Starbucksification of the world, there is often still some confusion over what it actually is – largely due to “espresso roasts” available on supermarket shelves everywhere. First, and most importantly, espresso is not a roasting method. It is neither a bean nor a blend. It is a method of preparation. More specifically, it is a preparation method in which highly-pressurized hot water is forced over coffee grounds to produce a very concentrated coffee drink with a deep, robust flavor. While there is no standardized process for pulling a shot of espresso, Italian coffeemaker Illy’s definition of the authentic espresso seems as good a measure as any:

A jet of hot water at 88°-93°

C (190°-200°F) passes under a pressure of nine or more atmospheres through a seven-gram (.25 oz) cake-like layer of ground and tamped coffee. Done right, the result is a concentrate of not more than 30 ml (one oz) of pure sensorial pleasure.

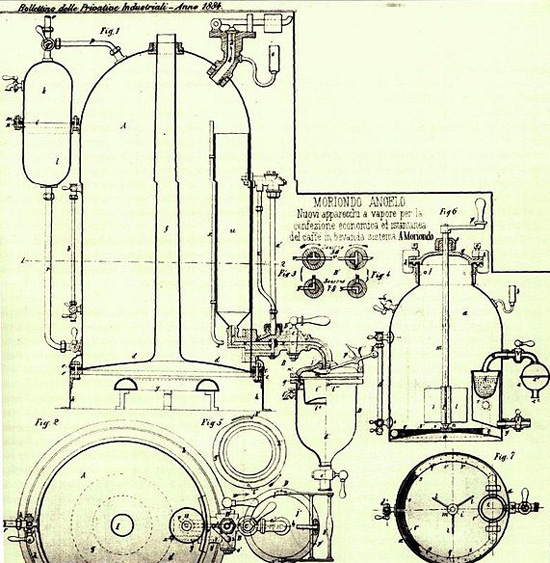

For those of you who, like me, are more than a few years out of science class, nine atmospheres of pressure is the equivalent to nine times the amount of pressure normally exerted by the earth’s atmosphere. As you might be able to tell from the precision of Illy’s description, good espresso is good chemistry. It’s all about precision and consistency and finding the perfect balance between grind, temperature, and pressure. Espresso happens at the molecular level. This is why technology has been such an important part of the historical development of espresso and a key to the ongoing search for the perfect shot. While espresso was never designed per se, the machines –or Macchina– that make our cappuccinos and lattes have a history that stretches back more than a century.

For full article please visit www.smithsonianmag.com

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)